Journals & bibliographic style

The first time I ever saw anyone do an uncontrolled jig of sheer appreciative agreement while sitting in a conference presentation room chair was last week. I may be immodest for saying so, but it was in response to a comment of mine. I said that academic journals should not ask authors to make formatting conversions of any kind in order to submit an essay. I heard at least one “huzzah!” in addition to seeing the jig.

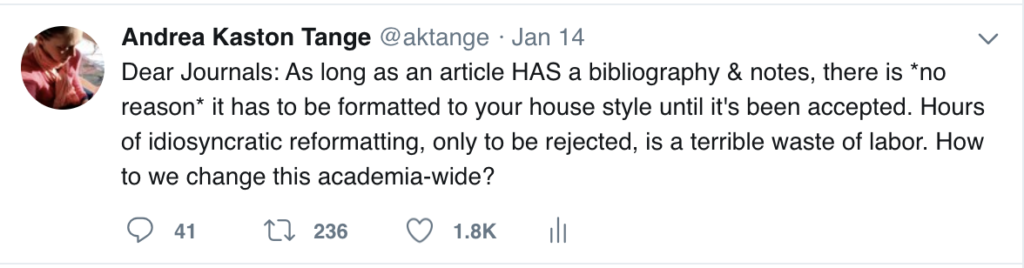

And so, because I’m trying generally to do more than just grump about things, yesterday I tweeted the same. There are journal editors amongst my mutuals, and I was thinking perhaps I could start some real conversations. The last twenty-four hours have been a fascinating ride, let me tell you.

With predictable, exhausting certainty, the Men You Don’t Know On The Internet came out in force to make one of three points. Over and over. Even when the guy above them had just made the same point and I’d responded politely with a reasonable counter.

Option 1: Just say no. “Just ignore these requirements; I do, and it always works out just fine for me” is a common refrain that, in fact, does nothing to acknowledge that only some people will feel authorized to flout the rules without fear of repercussions. And those people will be vastly disproportionately white and men.

Meanwhile scholars of color, women, and early career researchers are filling my mentions with stories of papers getting rejected due to mis-formatting; being returned without being read on the grounds of citation issues; being returned with specific reformatting requests as a condition of being sent out for peer review; being desk-rejected without any feedback after the formatting work had been done on request; and being sent out for peer review only to be rejected with no other comments than notes about citation irregularities.

Clearly, whether one’s sense of self-importance is sufficient to bolster sending out an article heedless of a journal’s formatting rules, journals themselves are not uniformly in agreement that citation style is irrelevant to an initial consideration of the ideas in a piece of scholarly work. And they are not uniformly distinguishing for their reviewers that substance is more important than citation style in deciding on a submission’s acceptance.

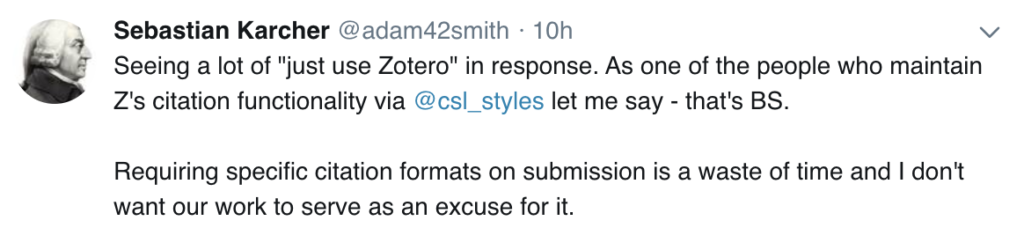

Option 2: Just use Zotero. “or Mendeley, or EndNote, or LaTeX (only for the sciences), or some other citation management system, which will magically do conversion for you, and by the way did you know these are all free, so what are you complaining about?”

YES! There are technological fixes for the problem of translating from one citation format to another, and thank goodness for automation. BUT there are also limitations. First, you have to have input your sources (often time-consuming, and not intuitive) into the system in the first place, which doesn’t help for this one paper that is coming out of a project that predates the existence of these systems. Second, the format you need has to be a commonly recognized major one and not Our Adorably Quirky House Style™ which is in fact what many journals use. And finally, even if you can convert the bibliography, these systems still leave you with the problem of idiosyncratic ways of citing material within the body of the text, parenthesis, footnotes, or endnotes, again formatted in OAQHS™.

There are also ethical reasons not to do this, as this delightful weighing-in points out:

As did those who wrote thoughtful replies about why substituting a technology answer for a problem that is not fundamentally one of technology, but of what people/journals expect of other people, is also not good practice.

Option 3: There should just be one formatting system for everything. But here’s the thing: format variations are purposeful. Fields that rely on experiments use parenthetical citations to track the chronology of related studies. Fields that rely on archives tend to prefer footnotes, for readers’ ease moving between supplemental information about primary source material and theorizing. So it’s hard to imagine how a single system would actually serve all disciplines well. Far better to urge, first, that journals with idiosyncratic styles abandon them for commonly accepted ones in their primary fields; and second, that it become common practice not to require formatting until after peer-review and acceptance.

I wonder if professional organizations like the MLA and AHA, or the boards of journal editors might not draft or endorse some kind of best practices statement around such an issue. I got a lot of responses to my tweet from editors, and some journal accounts, saying some version of “we couldn’t agree more, and we would never subject authors to this kind of policing, which seems a mean power move,” which makes me think such a wide-scale statement could perhaps be possible.

In my initial remarks on that conference panel, I was arguing that academic labor and systems are difficult enough that we ought to get rid of needlessly burdensome elements, and that I thought this was a real issue of access. After acceptance, of course, one should have to convert notes, references, and bibliographies, but not just to have an article considered, as this is hours of tedious work with no guarantee of payoff.

Several people came up to me afterwards to say they couldn’t agree more–at least a few who noted they didn’t feel comfortable saying so aloud during the session for reasons of how that might expose them (ECRs) to unwanted scrutiny. The world of academic labor is now nearly impossible to navigate; surely, given the weight that publications carry in the process of securing jobs, we could make this one small piece of the world a little easier to get through?